Excerpt

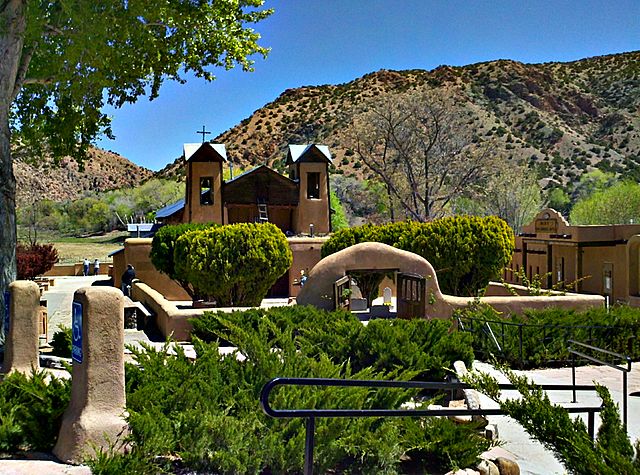

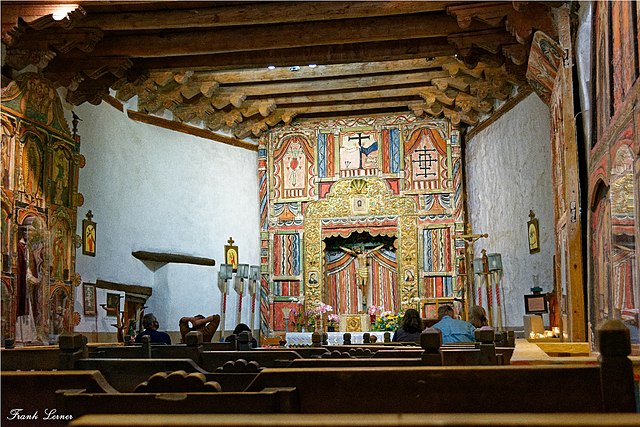

The face of the adobe church was dark, the courtyard shadowy under an ebony sky varnished with moonlight. She waited, leaning a hand on the rough wood arch, scanning humps and edges, stiffening against the freeze-dried norteña night. Nothing moved. Was this Churro’s idea of a joke? She should have taken the money to cover her wasted time. But a chorus of faithful crickets chirped an unceasing rhythm that said ‘clock-time is an illusion,’ ‘the only reality is flow.’ Lulled her to poise at the courtyard entrance, noticing chilly breaths sawing at her throat, feeling the weight of quiet on her eardrums, jazzed by the crickets and a thread of lapping water. The space felt crystalline, sacred. What difference did it make if Marcos showed or not?

Then she heard a car engine that stopped. She walked to the middle of the courtyard and paused by a rough hewn cross on an adobe base.

“Marcos?” she called out. “Churro sent something for you. If you answer a few questions I’ll turn it over to you.”

Her words seeped into the night. Chill air rising off the flagstones numbed her fingertips.

“Marcos? I’m leaving with the key Churro sent for you if you don’t come out.” A misshapen overfull moon shot beams at the courtyard leaving the facade of the church in darkness. After another pause she turned to leave.

“Wait.”

She spun around, peered at the church. A dark form emerged near the corner of the church.

“Are you…?”

“Exactly. The one who nearly took the hit for you when that sicario visited Paco’s.”

“Sorry about that. I had no idea that dude would—”

“I know. You’re blameless. It’s all just bad luck.”

He moved briefly through moonlight to disappear back into shadow on the other side of the church.

“You got the key?”

“Questions first.”

“Listen, I got no idea where Deandra is.”

“I know where Deandra is. That’s not what I want to know. Things have changed, Marcos. The stakes have gone up.”

“Look, I know the fam is worried sick about me. You tell ‘em I’ll lay low with Grifo in the Burque till things quiet down up here.”

At that moment, tires rolled over the gravel in the parking lot at the entrance to the compound. Marcos burst into the central area of the courtyard, his wiry silhouette suddenly splashed with ivory light.

“Gimme the key, quick.“

Minoa heard steps, spun around. Shots pinged off the adobe facade of the church, ricocheted off paving stones. Marcos doubled over and slumped to the ground.

New Mexico Curiosities

The rise in popularity of cars modified to hang low resulted in a backlash: the California vehicle code made it illegal to operate any car modified so that any part was lower than the bottoms of its wheel rims. In 1959, mechanic Ron Aguirre found a way to bypass the law by installing hydraulics that could raise and lower a General Motors X-frame chassis by flipping a switch.

Today lowrider types include ‘bombs’ (large, rotund American cars ca. 1930–1955), ‘originals’ (old cars restored to their original condition), ‘hoppers’ (cars outfitted with hydraulic lifters that allow them to bounce and jump), and ‘hot rods’ (classic American cars modified with large engines).